How to Build an Agent in JavaScript

• by • in categories: JavaScript, web development

This is a talk I gave at MelbJS on 13 August 2025.

Here’s a video version:

The final source code of the sample project is here.

If you prefer reading, read on! The following is a lightly-edited transcript of the video above:

You can see on my title slide here that I’m also crediting Thorsten Ball because in the spirit of AI technology, I borrowed Thorsten’s blog post without permission in order to help me generate this talk. I hope he doesn’t mind.

This is the blog post in question, How to Build an Agent, or: The Emperor Has No Clothes. It’s on the Amp Blog. Amp is an agentic coding tool from Sourcegraph. And this blog post came to my attention at the Web Directions Code Leaders conference in Melbourne in early 2025, where speaker Geoffrey Huntley, who had recently gone to work at Amp, mentioned this as, for his money, the blog post of the year.

He said, if you were trying to get your head around or come to grips with this, this new LLM powered coding tool landscape, that this was the blog post to read.

And when we talk about those tools, we’re talking about these things. This is the logos of Cursor, Zed, Windsurf, Amp, Claude Code and GitHub Copilot. And just because of how fast these things are moving right now, by the time I publish this video, it’s likely there are two more logos that belong on this slide and maybe one of these companies is already out of business.

That’s how fast these things are going, and that speed of evolution is one of the factors that makes this kind of technology really intimidating. It seems to work by magic. It’s progressing faster than our ability to understand how it works. But, the point of this blog post is that building a small and yet highly impressive agent doesn’t even require elbow grease.

You can do it in less than 400 lines of code, says Thorsten, most of which is boilerplate. I’m going to show you how right now we’re going to write some code together and go from zero lines of code to, oh wow, this is a game changer.

Pencils Out!

Permalink to Pencils Out!

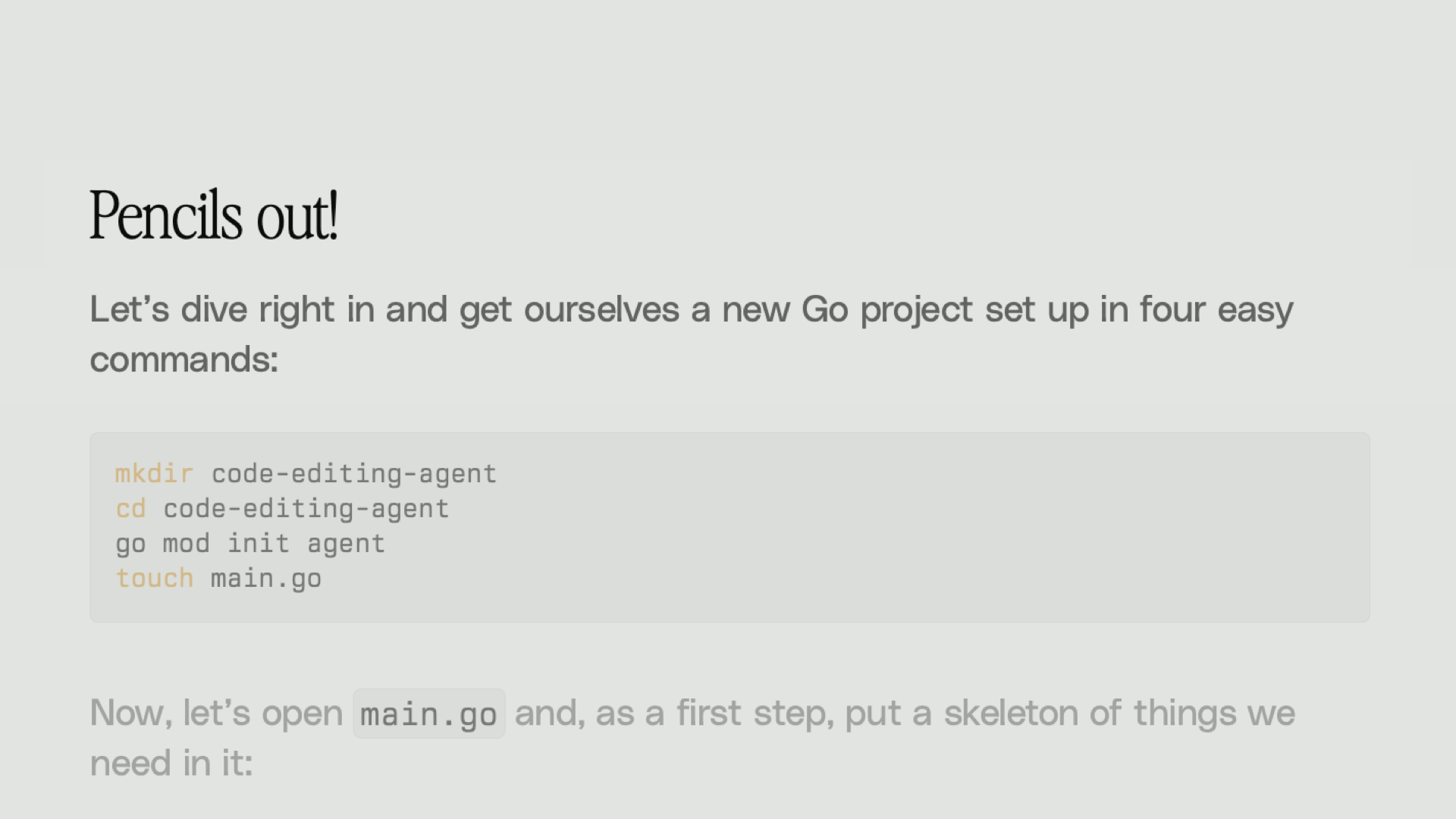

And so the blog post invites us to get our pencils out and to follow along, and it starts by creating a new Go project.

Now, this is where it, uh, it, uh, presented a bit of a speed bump to me because Go is not a language I know well, or really even at all. I mean, I know what it is. I know what it looks like. I’ve never used it to build anything so casually using it to explore a new technology would be like placing a challenge in front of a challenge.

And so looking at this, I thought, you know what? I am going to try to follow along in a language that I do know well, which, for today’s purposes will be JavaScript written in TypeScript. And so that’s what I’ve done. With this talk, I have translated ths blog post, which is excellent, but I’ve changed all of the code into TypeScript, for an audience that knows that language well.

So let’s get started. This is the index.js file, the startup file for a Node.js command line app:

import { AnthropicVertex } from "@anthropic-ai/vertex-sdk";

import * as readline from "readline/promises";

import { Agent } from "./agent/agent.js";

const projectId = "cross-camp-ai-enablement";

const region = "us-east5";

main();

async function main() {

const client = new AnthropicVertex({

projectId,

region,

});

const agent = new Agent(client, getUserMessage, showAgentMessage);

await agent.run();

}

async function getUserMessage(): Promise<string> {

// Create readline interface for user input

const rl = readline.createInterface({

input: process.stdin,

output: process.stdout,

});

// Prompt user for input

const userMessage = await rl.question("\u001b[94mYou\u001b[0m: ");

// Close the readline interface

rl.close();

return userMessage;

}

function showAgentMessage(message: string): void {

console.log(`\n\u001b[93mClaude\u001b[0m: ${message}\n`);

}

It has a main function here, and the first thing that function does when it starts up is it creates a client for the Anthropic Vertex service. So Anthropic is the company that makes the Claude LLM models, and Vertex is Google’s hosting of LLM models. It’s its service for providing access to LLM models.

So the Anthropic Vertex client lets me use the Anthropic models on the Google Vertex service. This happens to be the most convenient way for me to access a Claude model programmatically at Culture Amp because we use Google Vertex to host our, uh, our models for development purposes. I specify the project ID and the region, and it will get my credentials from the environment.

But basically I have created a connection to the Anthropic LLM model here as a client. And then I pass that client along with two other things to this Agent object there or class. This is a class that we are going to create. It is the body of our program, and we are going to instantiate that class, and then on the resulting agent object, we are going to call the run method.

So this Agent class takes three things, the Anthropic client that we’ve provided, a getUserMessage function and a showAgentMessage function.

So getUserMessage is doing some pretty standard Node.js stuff to present a prompt to the user with some nice shell colors. And when the user types a message and hits Enter, it will get that in this user message string, which it will return.

And the showAgentMessage is really just a console.log, again using some escape sequences here to present responses from Claude in a nicely colored header.

So we pass those three things into the Agent and then we run it. So let’s look at the Agent.

import { AnthropicVertex } from "@anthropic-ai/vertex-sdk";

import { Anthropic } from "@anthropic-ai/sdk";

import { BadRequestError } from "@anthropic-ai/vertex-sdk/core/error.mjs";

export class Agent {

constructor(

private client: AnthropicVertex,

private getUserMessage: () => Promise<string>,

private showAgentMessage: (message: string) => void,

) {}

async run() {

// TODO

}

}

This is our agent.ts file. It is as promised a TypeScript class with a constructor that takes those three things, the client, the getUserMessage, the showAgentMessage, and then it will have a run method, which to begin with just says, TODO.

So, what are we gonna make this Agent do?

Well, the first thing we wanna make it do is to provide a chat experience. This is how we will give our agent instructions and receive feedback back from that agent. So we would like for example, to say, Hi Claude, my name is Kevin, and have it send that up to the Claude model. The Claude model might reply with a message that we want to present on screen.

Hello, Kevin. It’s nice to meet you. How are you doing today? Is there something I can help you with?

And then we might respond with what’s my name, just to test if it’s paying attention, but out of the box it might say something like, I don’t have access to your personal information, including your name, unless you’ve shared it with me in our conversation.

And this will happen because all of these LLM services are completely stateless, so every request you send to it is completely separate. It has no memory from one request to the next.

As web developers, this should be familiar. This is how web servers work by default as well. So if we want to carry on a conversation, we are going to need to provide it some way to remember the conversation so far.

So what we do instead to prevent it from saying New phone, who dis? is, when we send our first message and it replies back, we will take that reply into a record of the conversation so far.

So this is a reminder. You said this, and now I’m gonna ask this follow-up question. And when we send this question to the LLM, we actually send the entire conversation so far as a list of messages and then it is able to reply, your name is Kevin, as you mentioned in your introduction.

This is how all LLM powered chat experiences work. The longer you chat with them, the more context you need to send, the larger the record of the conversation so far gets every time you send it with your next message. And this is one reason why chats get more and more expensive in the number of tokens they use, the longer that they run.

So how do we implement this back and forth in our run function?

async run() {

const conversation: Anthropic.MessageParam[] = []

console.log("Chat with Claude (use 'ctrl-c' to quit)")

while (true) {

const userMessage: Anthropic.MessageParam = {

role: "user",

content: await this.getUserMessage(),

}

conversation.push(userMessage)

try {

const result = await this.runInference(conversation)

conversation.push(this.messageToMessageParam(result))

for (const message of result.content) {

switch (message.type) {

case "text":

this.showAgentMessage(message.text)

break

}

}

} catch (error) {

console.error("Error:", error)

}

}

}

private runInference(

conversation: Anthropic.MessageParam[],

): Promise<Anthropic.Message> {

return this.client.messages.create({

model: "claude-3-7-sonnet@20250219",

max_tokens: 1024,

messages: conversation,

})

}

private messageToMessageParam(

message: Anthropic.Message,

): Anthropic.MessageParam {

return {

role: message.role,

content: message.content,

}

}

Well, we will start by creating this conversation list. So it will be an empty array of Anthropic messages. Ut’s empty because the conversation has yet to begin. We’ll display an introductory message saying, Control-C to quit, and then we go into this while true block. So while a while true loop will just run over and over again until the user exits the program with Control C.

We will then begin by getting the user’s first message, using that getUserMessage method that we passed into the constructor. And when we get that message, we will bundle it up into this object with a role user and the content of the message. This is what these Anthropic messages need to look like. And we will push it into the conversation. The conversation will begin with the user’s first message.

We then pass the entire conversation into this runInference method, which we have implemented. It’s a very short method. All it does is send the conversation in its entirety to the Claude model using the client that was passed into the constructor.

We specify Claude 3.7 Sonnet here, and we say that we want it to reply with a maximum of 1,024 tokens.

That will result in a response from the LLM, which we receive in our while loop.

First of all, we translate that response into that same MessageParam object format, which we do with this messageToMessageParam function. Nothing too complicated going on there.

And then we push that into our conversation. Our conversation now includes our request and the initial response. We then go through the messages in the response and look for any that are a text message from the LLM, and any text messages that we get from the LLM we will display to the user with showAgentMessage, that function that was passed into our agent’s constructor with the message text.

And that’s it. Uh, we then start the while loop over again by asking the user to contribute another message to the conversation. And on it goes.

Let’s demo this. I’ve got all of this code so far in my project here, and I’m gonna run it with pnpm agent.

❯ git checkout demo1

❯ pnpm agent

vertexai-playground@1.0.0 agent /Users/kyank/Developer/how-to-build-an-agent-in-javascript

pnpm build && node dist/agent.jsvertexai-playground@1.0.0 build /Users/kyank/Developer/how-to-build-an-agent-in-javascript

tscChat with Claude (use ‘ctrl-c’ to quit)

You: My name is Kevin Yank.Claude: Hello, Kevin Yank! It’s nice to meet you. Is there something I can help you with today?

You: Suggest some nicknames for me.

Claude: Here are some potential nicknames for Kevin Yank:

• Kev

• K.Y.

• Yanker

• K-Yank

• Kevster

• Captain K

• The Yank

• K-Dog

• Yanky

• KevboThese are just suggestions - nicknames usually work best when they reflect your personality or come about naturally from friends and family!

You:

Now, let’s say my name is Kevin Yank.

It creates that conversation list, sends it to the LLM, receives the response, adds the response to the conversation, and then displays it on the screen. Hi, Kevin Yank. Nice to meet you. Okay, great. Now let’s test if it remembers my name.

I’ll ask it to suggest some nicknames for me. Just a little risky. Let’s see what it comes up with. All right. There we go. Uh, Captain K, that’s a new one. No one has ever called me Captain K. Okay. Um, yeah. Interesting.

Let’s, uh, move on from that very swiftly.

And the blog post says, okay, let’s move on, because the nicknames suck.

They do indeed.

And this is not an agent yet. What is an agent? Here is Thortsten’s definition: an LLM with access to tools, giving it the ability to modify something outside the context window.

The context window is the technical name for that conversation list. It is the window of things that we will remind the LLM of every time we send it a request.

Right now, all the LLM is empowered to do is to contribute messages to that list. So giving it tools that let it do other things is how we will turn it into an agent.

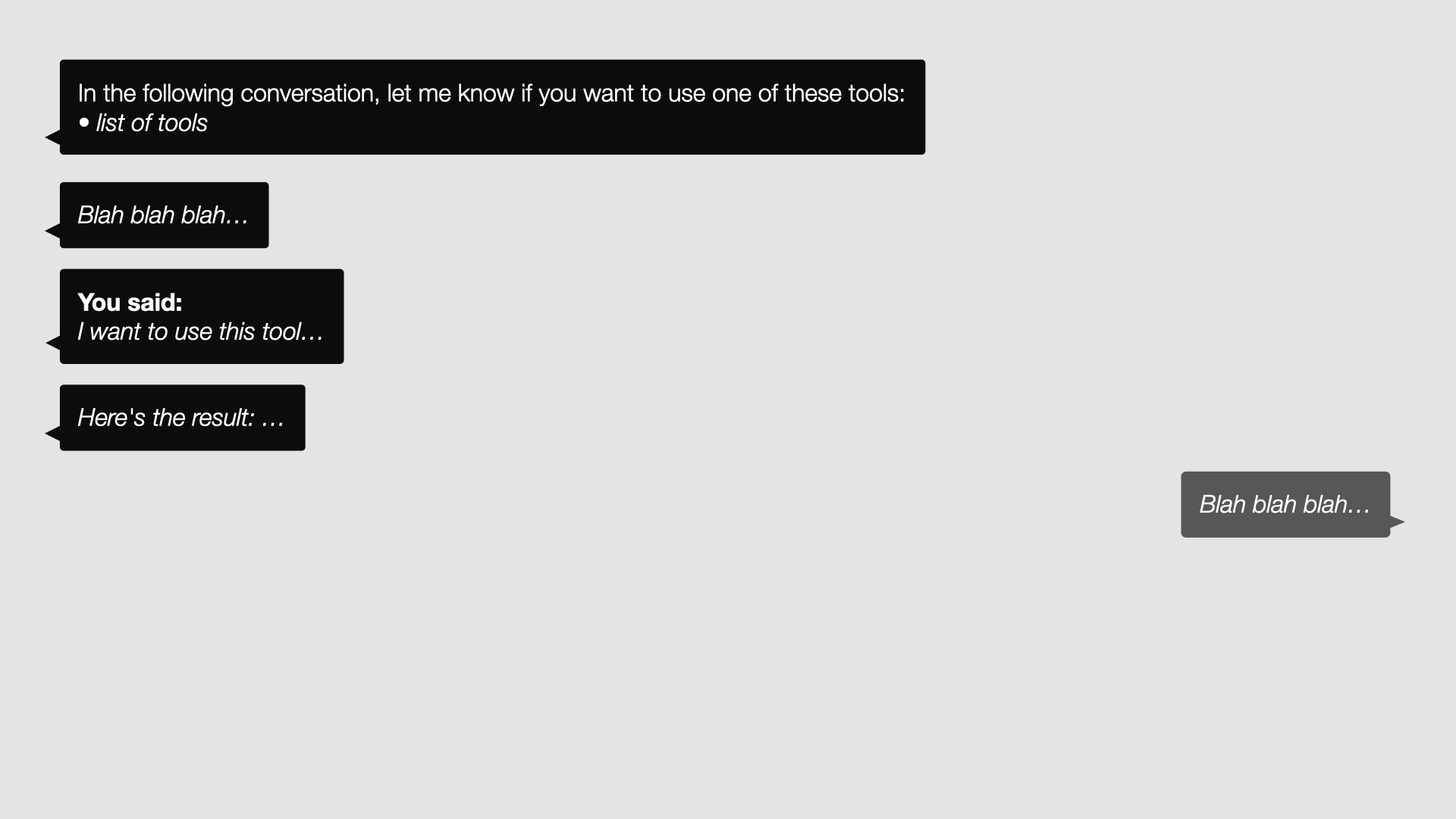

So let’s think about our first tool. What is a tool? Well, it says the basic idea is this. You send a prompt to the model that says it should reply in a certain way. If it wants to use a tool, then you as the receiver of that message, use the tool by executing it and replying with the result.

That’s it. Everything else we’ll see is just an abstraction on top of this concept.

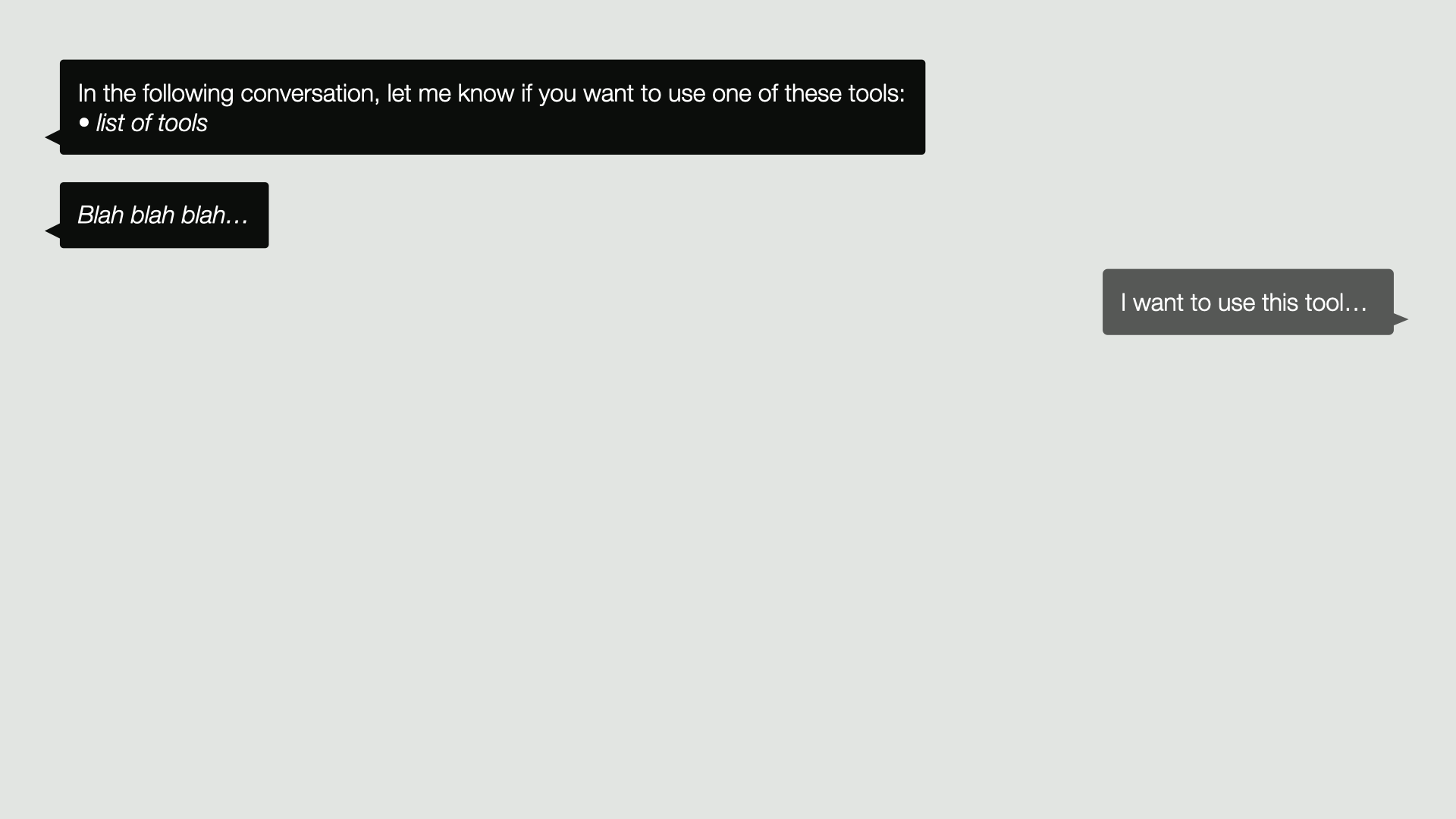

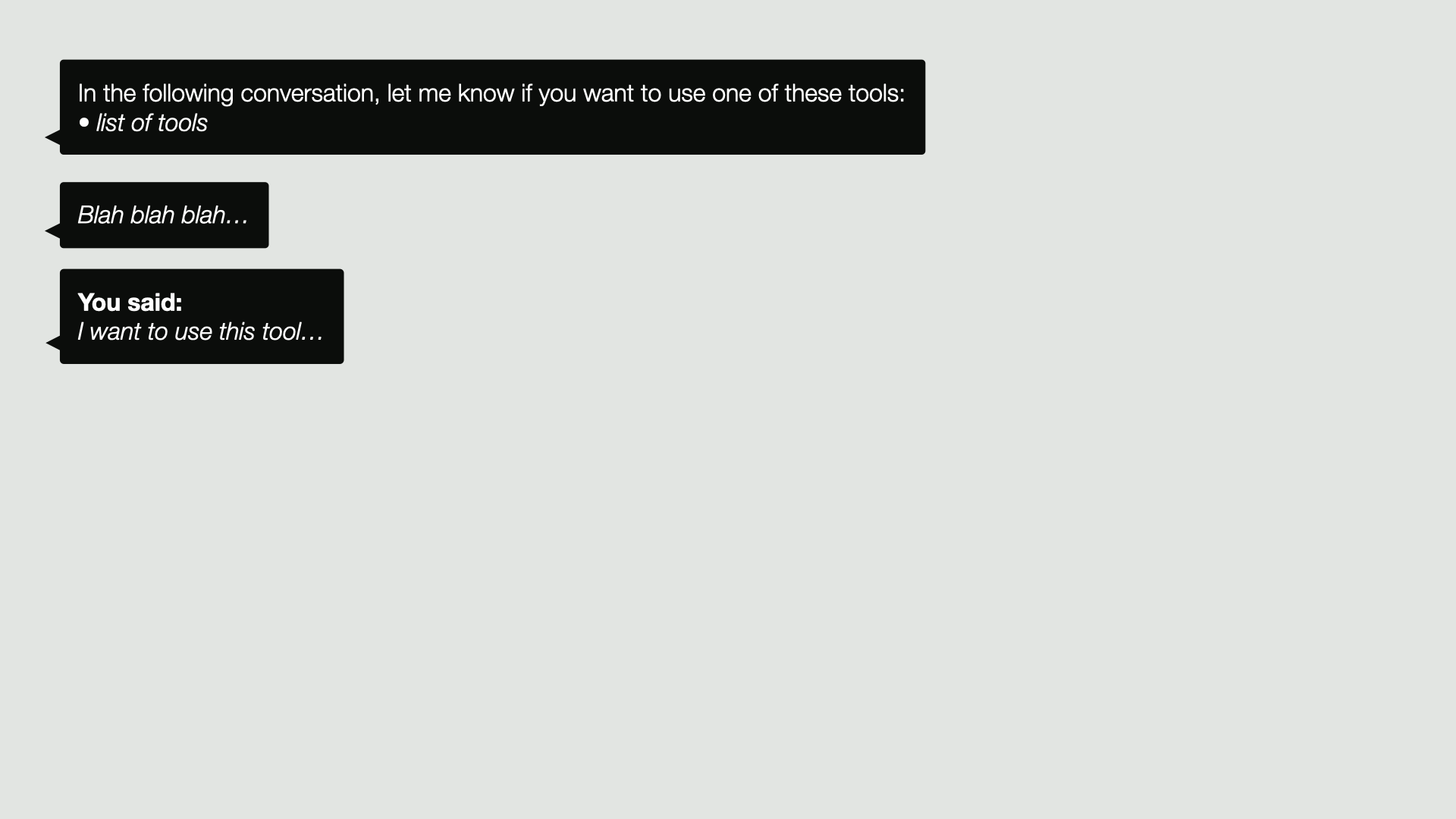

So replaying this in our diagram of the conversation, we might start the conversation by saying, in the following conversation, let me know if you want to use one of these tools, and then we list all the tools that are available. Then blah, blah, blah. We have a conversation, and at a certain point, the LLM may reply with, I want to use this tool,

in which case, as usual, we record that as a message in the conversation. We then follow its request. We run the tool for it and add the response or the result of running that tool to the conversation.

We then send the conversation back to the LLM as usual, and it will continue with the knowledge of what resulted from its tool call. That’s it.

In his blog post, Thorston says, this is like when you’re talking to a human, you might say in the following conversation, wink if you want me to raise my arm. And in a funny sort of way, you have now given that other human the power to raise your arm. They can’t literally raise your arm, but they can ask you to and you will do it for them.

And that is how an agent works. We tell the LLM some things we are willing to do for it, and then it will let us know when it wants us to do those things.

So we can actually demonstrate this with the code we’ve already written.

You: When I ask you about the weather in a given location, I want you to reply with

get_weather(<location_name>). I will then tell you what the weather in that location is. Understood?Claude: I understand. When you ask me about the weather in a specific location, I’ll respond with

get_weather(<location_name>). Then you can provide me with the weather information for that location, and we can continue our conversation from there.You: What’s the weather in Melbourne, Australia?

Claude: get_weather(Melbourne, Australia)

You: Sunny and 15 degrees C

Claude: Thank you for providing that information. It sounds like a pleasant day in Melbourne, Australia - sunny with a temperature of 15 degrees Celsius. That’s what I’d consider mild weather - cool enough to need a light jacket but with nice sunshine. Perfect for spending some time outdoors if you have the opportunity!

You:

So back in our conversation about the nicknames, I’m gonna say, when I ask you about the weather in a given location, I want you to reply with get_weather(<location_name>). I will then tell you what the weather in that location is. Understood?

So we’re teaching it about a tool. It says, I understand. So let’s try it out.

What’s the weather in Melbourne, Australia?

That’s where I happen to be, on the land of the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung people.

It says get_weather. So it is actually sending us a tool call.

So we would now go to the Bureau of Meteorology website, look up the weather and respond. It’s sunny and 15 degrees C.

Thank you for letting me know. Sunny and 15 degrees Celsius in Melbourne, Australia. Anyway, it goes on. It asked us to look up the thing, the answer to the question we asked it, we looked up the answer for it. It then repeated that answer because it now has that knowledge.

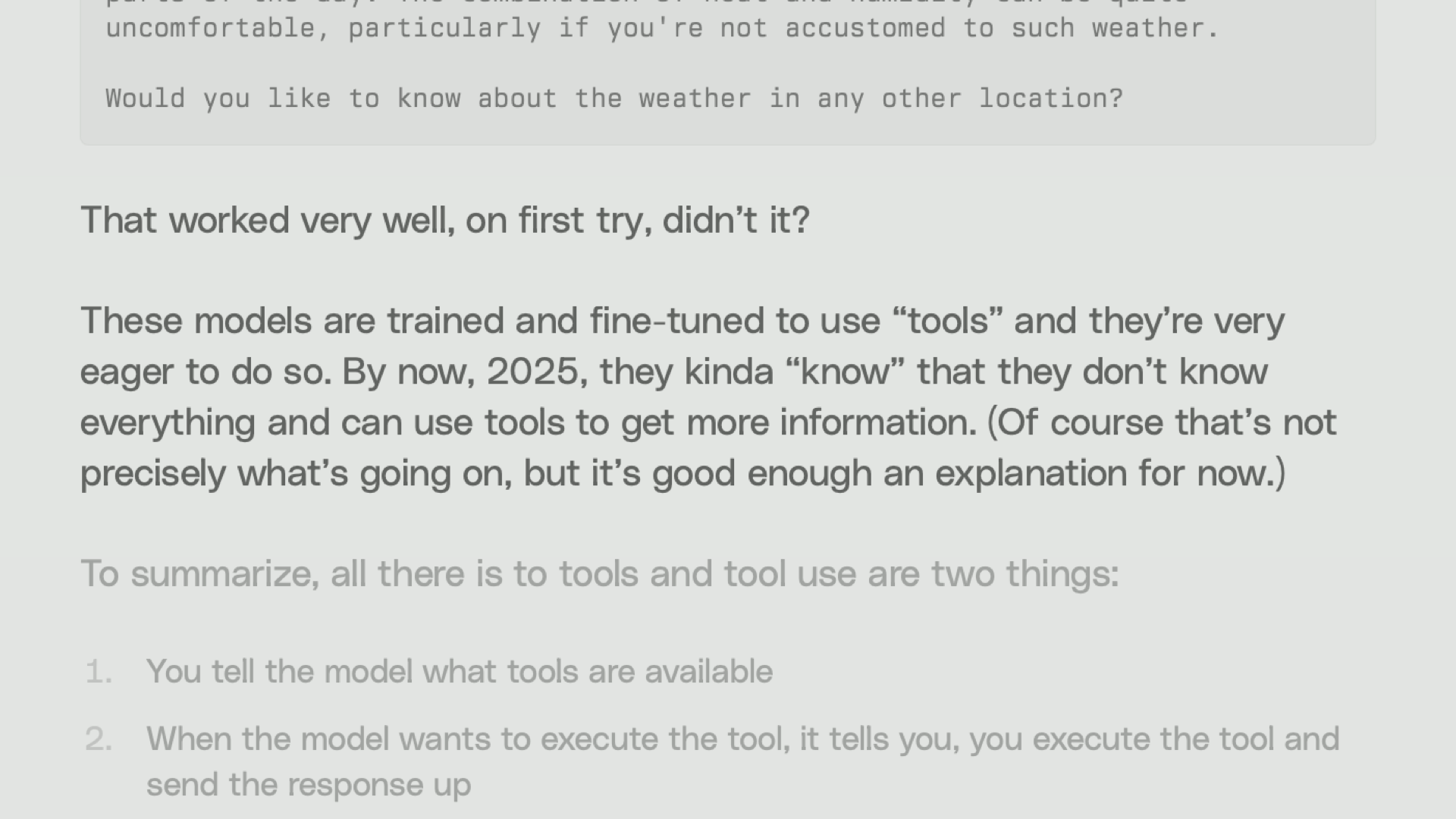

That is how a tool works in an AI agent. Thorston in his blog post says That worked very well on first try, didn’t it? These models are trained and fine tuned to use tools, and they’re very eager to do so. By now in 2025, they kind of know that they don’t know everything and can use tools to get more information.

Of course, that’s not precisely what’s going on, but it’s a good enough explanation for now.

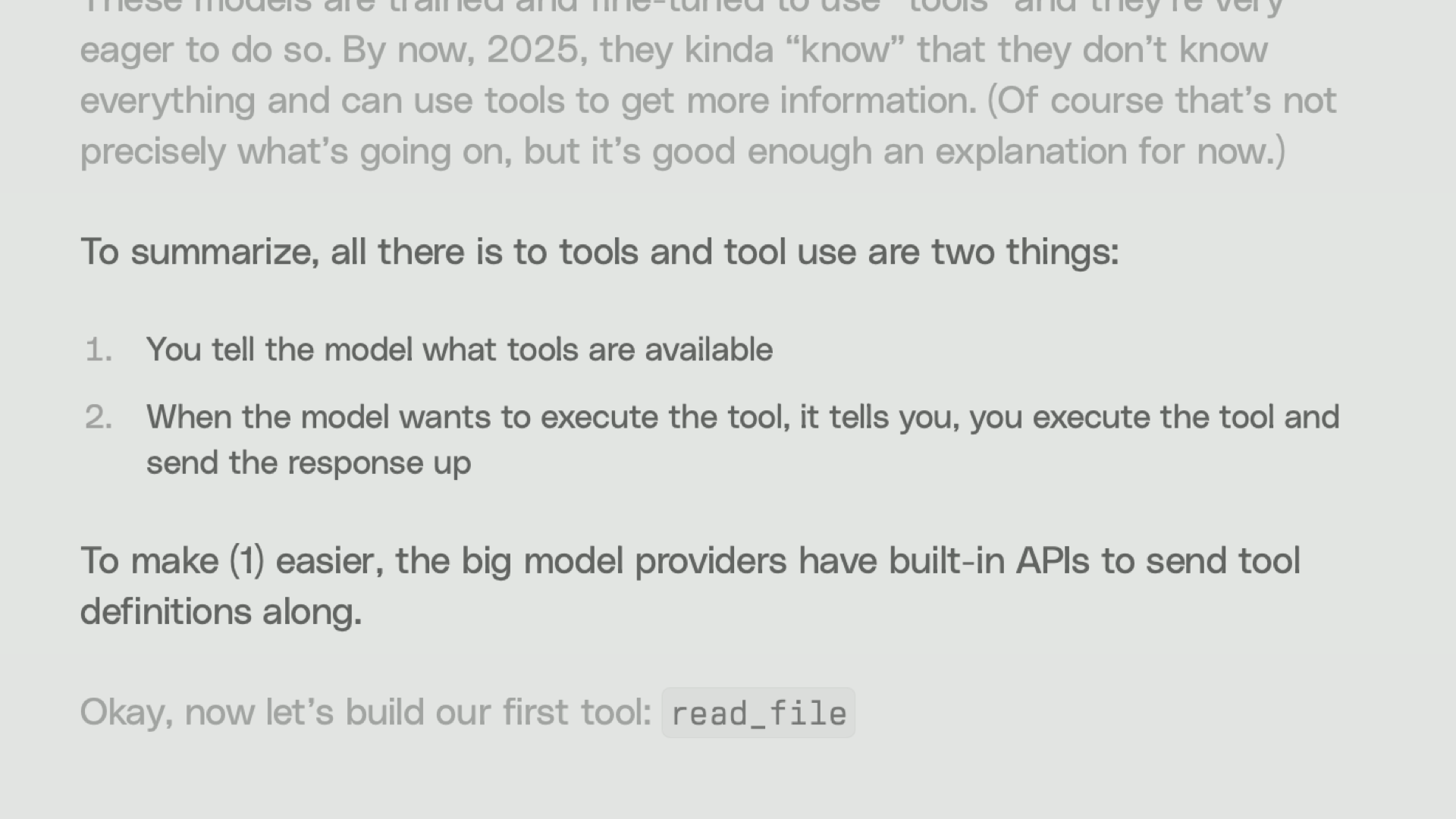

To summarize, all there is to tools and tool use are two things: You tell the model what tools are available. Then when the model wants to execute the tool, it tells you, you execute the tool and send the response up.

To make step one easier, the big model providers have built-in APIs to send tool definitions along with your requests.

The read_file tool

Permalink to

The read_file tool

So let’s actually build a tool in our code. This will be the read_file tool. And in order to define the read_file tool, we’re going to use the types that the Anthropic SDK suggests, but keep in mind, under the hood, this will all end up as strings that are sent to the model.

It’s all wink if you want me to use read_file.

import { Anthropic } from "@anthropic-ai/sdk";

export type ToolDefinition = {

name: string;

description: string;

input_schema: Anthropic.Tool.InputSchema;

func: (args: any) => Promise<string> | string;

};

So the first thing we’ll do is because this is a TypeScript program, we will write a type that defines what a ToolDefiniton is. A tool is defined by three things: a name, which is a string, a description, the instructions for what that tool does, and when the model should use it, and an input_schema. This is a schema that says what arguments or parameters are required when sending a request to run this tool.

And the last thing is the function. That’s not there for the LLM; that’s there for us. When the LLM asks us to run this tool, this is the function that we will call to do the work for it. It will return either a string or a promise of a future string if it needs to do anything asynchronous.

export class Agent {

constructor(

private client: AnthropicVertex,

private getUserMessage: () => Promise<string>,

private showAgentMessage:

(message: string) => void,

private showToolMessage:

(message: string) => void,

private tools: ToolDefinition[],

) {}

private runInference(

conversation: Anthropic.MessageParam[],

): Promise<Anthropic.Message> {

const anthropicTools: Anthropic.ToolUnion[] =

this.tools.map((tool) => ({

name: tool.name,

description: tool.description,

input_schema: tool.input_schema,

}))

return this.client.messages.create({

model: "claude-3-7-sonnet@20250219",

max_tokens: 1024,

messages: conversation,

tools: anthropicTools,

})

}

So then in our Agent, we will add a couple of things to the constructor. We will have a showToolMessage. This is something that we will call when we are, um, when the LLM sends us a message to run a tool. And finally a list of tools, which is an array of these ToolDefinition objects.

Our runInference function that we use to send requests to the LLM gets a little bit bigger. Before we were just sending the conversation, but now we are also sending this list of tools and that list of tools we build up by taking our list of tool definitions, and basically stripping off those functions, which I mentioned are just for us to use. We’re passing along just the name, the description, and the input_schema. Those three things are all that the model needs to know about to use our tools.

import tools from "./agent/tools/index.js"

async function main() {

⋮

const agent = new Agent(

client,

getUserMessage,

showAgentMessage,

showToolMessage,

tools,

)

await agent.run()

}

function showToolMessage(message: string): void {

console.log(

`\n\u001b[92mTool\u001b[0m: ${message}\n`

)

}

Now in our main function at the top of our program, we need to pass these two new things, showToolMessage, and tools to the Agent constructor.

The showToolMessage is just another console.log function that provides some nice formatting in a different color, and the list of tools we are importing from another file that looks like this.

import { readFileTool } from "./readFile.js";

export default [readFileTool];

This is just an export of a array with one item in it. So we have only one tool so far. It is the readFileTool that again, we import from another file and now we’re ready to actually write that tool.

import fs from "fs/promises";

import { existsSync } from "fs";

import nodePath from "path";

import { ToolDefinition } from "../types.js";

/**

* Tool for reading file contents

*/

export const readFileTool: ToolDefinition = {

name: "read_file",

description: `Read the contents of a given relative file path.

Use this when you want to see what's inside a

file. Do not use this with directory names.`,

input_schema: {

type: "object",

properties: {

path: {

type: "string",

description: `The relative path of a file in

the working directory.`,

},

},

required: ["path"],

},

func: async (args: any): Promise<string> => {

const path: string = args.path;

const resolvedPath = nodePath.resolve(path);

// Check if file exists

if (!existsSync(resolvedPath)) {

throw new Error(`File not found: ${path}`);

}

try {

return fs.readFile(resolvedPath, "utf-8");

} catch (error) {

throw new Error(error instanceof Error ? error.message : String(error));

}

},

};

Here’s what it looks like. Um, there is not very much code here, it is just a big object with those fields. We described the name, read_file the description, which is the instructions to the LLM. The input_schema, which says that there is a path argument that is required. It is a string, which is the relative path of a file in the working directory.

And then over on the right hand side is our function. This func, again, is the thing that we will call when we need to do the work of this tool. And its contents is really just plain Node.js file system stuff. We check if the file exists here with existsSync, and if it does, we read the file as a UTF-8 text file and return its contents as a string.

That’s it. That’s our tool for reading file contents.

So with that code added to our project, let’s try it out.

❯ git checkout demo2

❯ pnpm agent

vertexai-playground@1.0.0 agent /Users/kyank/Developer/how-to-build-an-agent-in-javascript

pnpm build && node dist/agent.jsvertexai-playground@1.0.0 build /Users/kyank/Developer/how-to-build-an-agent-in-javascript

tscChat with Claude (use ‘ctrl-c’ to quit)

You: What’s in src/agent.ts?Claude: I’ll check what’s in the src/agent.ts file for you.

You:

I’m going to check out this version and run the agent. And ask it what’s in src/agent.ts, which is that top level file with the main function in it. I’ll check the contents of the file for you, and then nothing happens.

Do you know why nothing happens? Well, the LLM is winking at us, but we are not yet paying attention to winks.

async run() {

const conversation: Anthropic.MessageParam[] = []

console.log(

"Chat with Claude (use 'ctrl-c' to quit)")

let readUserInput = true

while (true) {

if (readUserInput) {

const userMessage: Anthropic.MessageParam = {

role: "user",

content: await this.getUserMessage(),

}

conversation.push(userMessage)

}

try {

const result =

await this.runInference(conversation)

conversation.push(

this.messageToMessageParam(result))

const toolResults:

Anthropic.ContentBlockParam[] = []

for (const message of result.content) {

switch (message.type) {

case "text":

this.showAgentMessage(message.text)

break

case "tool_use":

const result = await this.executeTool(

message.id,

message.name,

message.input,

)

toolResults.push(result)

}

}

if (toolResults.length === 0) {

readUserInput = true

continue

}

readUserInput = false

conversation.push({

role: "user",

content: toolResults,

})

} catch (error) {

⋮

}

}

}

So back in our code, there’s something more we need to add here. This is our run function for the Agent. And inside of our while loop, we were previously responding to text messages by showing an agent message on the screen.

There is now a second kind of message that we need to recognize from the model, and that’s a tool_use message. And when that kind of message comes in, we will call our executeTool method that I’ll show you on the next slide. We pass in the request to execute a tool and get a result back. That result, we will push into a toolResults array, and then after processing all the messages from the LLM, if there are any tool results, then we can skip prompting the user for the next message because the next message that we wanna send to the LLM is the result of running the tool. We don’t need to also prompt the user to type something in. We push all all of the tool results into the conversation list and go back to the start of the while loop.

That’s it. That’s everything that’s changed here.

Now let’s look at the executeTool method.

private async executeTool(

id: string,

name: string,

input: unknown,

): Promise<Anthropic.ContentBlockParam> {

const tool = this.tools.find(

(t) => t.name === name)

if (!tool) {

return {

tool_use_id: id,

type: "tool_result",

content: `tool not found`,

is_error: true,

}

}

const toolDescription =

`${name}(${JSON.stringify(input)})`

this.showToolMessage(toolDescription)))

try {

return {

tool_use_id: id,

type: "tool_result",

content: await tool.func(input),

}

} catch (error) {

return {

tool_use_id: id,

type: "tool_result",

content: error instanceof Error

? error.message

: String(error),

is_error: true,

}

}

}

What it does is it looks through our list of tools to find the one with a name that matches the one requested by the model. If it doesn’t find such a tool, we will respond with this error object that the language model will recognize.

But if we do find the tool that was requested, then we create a string here to describe the tool request and show it on the screen to the user. And then the last thing we do is actually call the tool function with the provided inputs and put its result in this content field of this object, which is a tool result object that will go into the conversation record and be sent back to the LLM.

All right. Our missing pieces are in place now. Let’s try the demo again.

Oh, and before I. Ask it to do something. I’m gonna set something up here. This is, uh, a fun little thing that Thorston has in his blog post.

❯ git checkout demo3

❯ echo ‘what animal is the most disagreeable because it always says neigh?’ >> secret-file.txt

He’s gonna create a secret-file.txt file on my hard drive, and it contains a riddle. What animal is the most disagreeable because it always says neigh?

Now let’s run the agent and ask it:

❯ git checkout demo3

❯ pnpm agent

vertexai-playground@1.0.0 agent /Users/kyank/Developer/how-to-build-an-agent-in-javascript

pnpm build && node dist/agent.jsvertexai-playground@1.0.0 build /Users/kyank/Developer/how-to-build-an-agent-in-javascript

tscChat with Claude (use ‘ctrl-c’ to quit)

You: Claude, buddy, help me solve the riddle in the secret-file.txt fileClaude: I’ll help you solve the riddle in the secret-file.txt file. Let me first read its contents to see what we’re working with.

Tool: read_file({“path”:“secret-file.txt”})

Claude: I found the riddle! It’s a classic wordplay riddle:

“What animal is the most disagreeable because it always says neigh?”

The answer is a horse!

This is a pun-based riddle where:

- Horses make a sound that we call a “neigh”

- “Neigh” sounds like “nay,” which is a way of saying “no” or disagreeing

- So horses are “disagreeable” because they’re always saying “neigh/nay”

Was there anything else you wanted to know about this riddle?

You:

Claude, buddy, help me solve the riddle in the secret-file.txt file

It is going to read the file and there you go. It reads the riddle and comes up with the answer. The answer to this riddle is a horse, and at this point, Thorsten invites us to say, holy crap.

In fact, he uses slightly spicier language into the blog post.

Let’s take a deep breath and say it together. Ready? Here we go. Holy shit. You just give it a tool and it uses it when it thinks it’ll help solve the task. Remember, we didn’t say anything about if a user asks you about a file, read the file. We also didn’t say if someone looks, if something looks like a file name, figure out how to read it. No, none of that.

We say, help me solve the thing in this file, and Claude realizes that it can read the file to answer that, and off it goes.

Detour: human in the loop

Permalink to Detour: human in the loop

At this point, I got a little freaked out because I realized this program was giving access to read any file on my hard drive to this language model that I maybe shouldn’t trust.

And so I’m gonna take a slight detour here from Thorsten’s blog post and talk about human in the loop. I want to approve all of these tool calls because already they’re doing something potentially dangerous that I wanna make sure seems sensible to me.

import tools from "./agent/tools/index.js"

async function main() {

⋮

const agent = new Agent(

client,

getUserMessage,

showAgentMessage,

getToolConsent,

tools,

)

await agent.run()

}

async function getToolConsent(message: string):

Promise<boolean> {

const rl = readline.createInterface({

input: process.stdin,

output: process.stdout,

})

const consent = await rl.question(

`\n\u001b[92mTool request\u001b[0m: ${message}\n`

+ "\u001b[93mClaude\u001b[0m: Continue? [yes]: ",

)

rl.close()

return consent === "" ||

consent.toLowerCase() === "yes"

}

So instead of the showToolMessage function, we are going to pass to our Agent a getToolConsent function, which is a little more strenuous.

Instead of just doing a console.log, it is going to ask the user, here’s the tool request. Do you want to continue? Type yes or hit enter to continue. And if the user does anything other than hit enter or type yes, we will refuse to run the tool.

export class Agent {

constructor(

private client: AnthropicVertex,

private getUserMessage: () => Promise<string>,

private showAgentMessage:

(message: string) => void,

private getToolConsent:

(message: string) => void,

private tools: ToolDefinition[],

) {}

private async executeTool(

id: string,

name: string,

input: unknown,

): Promise<Anthropic.ContentBlockParam> {

const tool = this.tools.find(

(t) => t.name === name)

if (!tool) {

return {

tool_use_id: id,

type: "tool_result",

content: `tool not found`,

is_error: true,

}

}

const msg = `${name}(${JSON.stringify(input)})`

if (!(await this.getToolConsent(msg)))

return {

tool_use_id: id,

type: "tool_result",

content:

`User did not consent to tool execution`,

is_error: true,

}

try {

return {

tool_use_id: id,

type: "tool_result",

content: await tool.func(input),

}

} catch (error) {

return {

tool_use_id: id,

type: "tool_result",

content: error instanceof Error

? error.message : String(error),

is_error: true,

}

}

}

That’s what this looks like here in our, uh, execute tool method.

If the user doesn’t give tool consent, we return a tool result that’s an error saying the user did not consent to tool execution. Alright, so let us see how this works.

❯ git checkout demo4

❯ pnpm agent

vertexai-playground@1.0.0 agent /Users/kyank/Developer/how-to-build-an-agent-in-javascript

pnpm build && node dist/agent.jsvertexai-playground@1.0.0 build /Users/kyank/Developer/how-to-build-an-agent-in-javascript

tscChat with Claude (use ‘ctrl-c’ to quit)

You: Claude, help me solve the riddle in secret-file.txtClaude: I’ll help you solve the riddle in secret-file.txt. First, let me read the file to see what the riddle contains.

Tool request: read_file({“path”:“secret-file.txt”})

Claude: Do you want to continue? [yes]: noClaude: I apologize, but I need your permission to use the file reading tool to access the content of secret-file.txt. Once you give your consent, I’ll be able to read the file and help you solve the riddle it contains.

Would you like me to proceed with reading the secret-file.txt? Please confirm, and then I can help you solve the riddle inside.

You:

Uh, Claude, help me solve the riddle in the secret-file.txt file. Now, this time, instead of just going ahead and reading it, taking liberties, it actually asks if I want to continue and I can say no. And my refusal goes back as a part of the conversation and the model actually deals with this pretty well.

It says, I’m unable to access the file because I need your consent. Would you like me to read this file for you? If so, please confirm that I have your permission and I’ll help you solve the riddle inside. So, this is working great. Okay. I’m feeling more comfortable again. We can go back to the blog post.

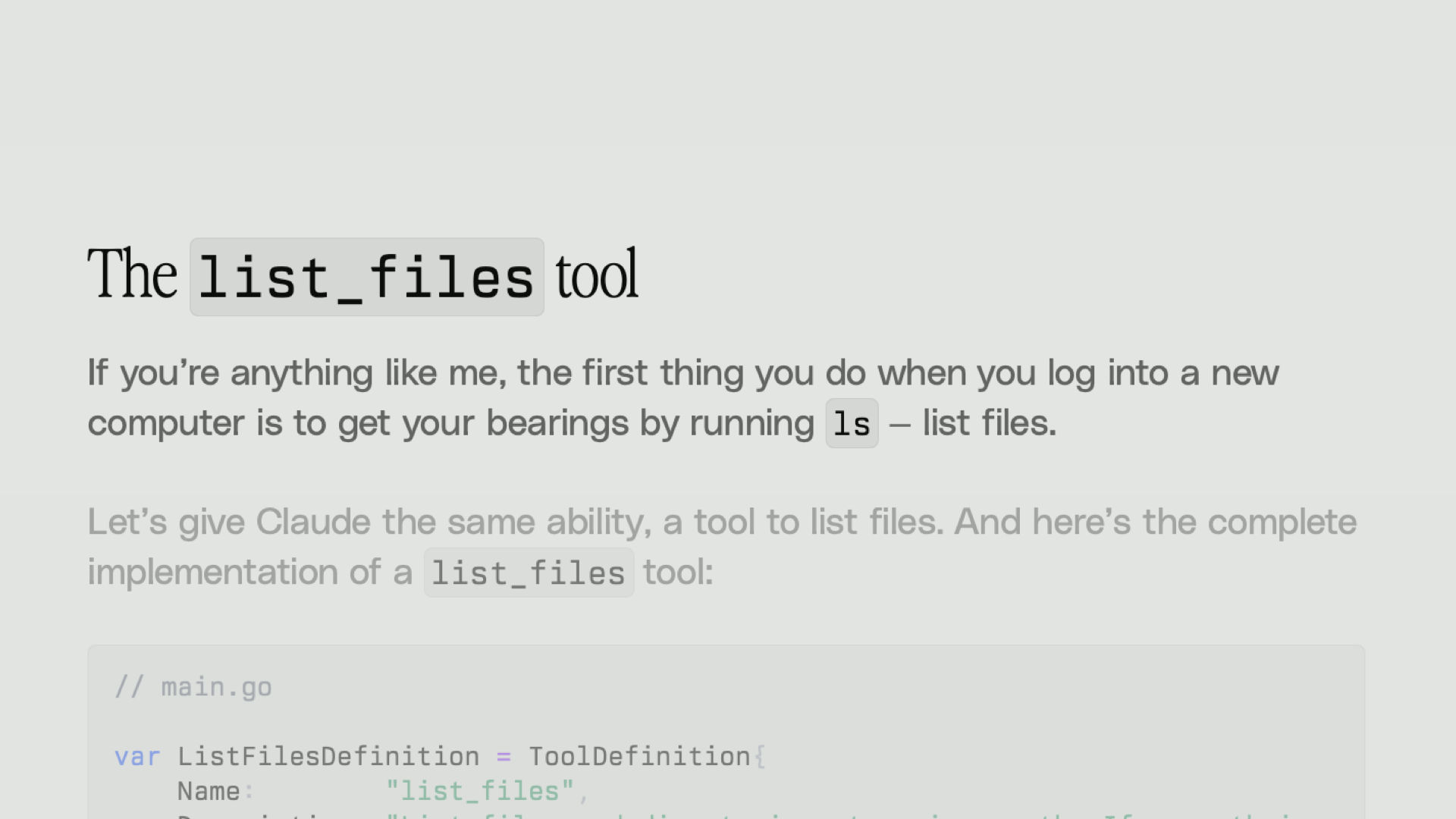

The list_files tool

Permalink to

The list_files tool

The next thing Thorston invites us to do is to create a list files tool.

If you’re anything like me, he says, the first thing you do when you log into a new computer is to get your bearings by running ls, list files. Let’s let our agent do that.

import { readFileTool } from "./readFile.js";

import { listFilesTool } from "./listFiles.js";

export default [readFileTool, listFilesTool];

We add a second file to our list of files here, and uh, we import that from a separate file and add it to our array.

import fs from "fs/promises";

import { existsSync } from "fs";

import nodePath from "path";

import { ToolDefinition } from "../types.js";

/**

* Tool for listing files in a directory

*/

export const listFilesTool: ToolDefinition = {

name: "list_files",

description: `List files and directories at a given path. If no

path is provided, lists files in the current

directory.`,

input_schema: {

type: "object",

properties: {

path: {

type: "string",

description: `Optional relative path to list files from.

Defaults to current directory if not

provided.`,

},

},

required: [],

},

func: async (args: any): Promise<string> => {

const path: string = args.path ?? ".";

const rPath = nodePath.resolve(path);

// Check if path exists and is a directory

if (!existsSync(resolvedPath)) {

throw new Error(`Directory not found: ${path}`);

}

const stat = await fs.stat(resolvedPath);

if (!stat.isDirectory()) {

throw new Error(`${path} is not a directory`);

}

try {

const dir = await fs.readdir(resolvedPath);

const entriesWithDirectoryMarkers = await Promise.all(

dir.map(async (entry) => {

const fullPath = nodePath.join(rPath, entry);

try {

const stats = await fs.stat(fullPath);

return stats.isDirectory() ? `${entry}/` : entry;

} catch (error) {

return entry;

}

}),

);

return JSON.stringify(entriesWithDirectoryMarkers);

} catch (error) {

throw new Error(

`Error reading dir: ${

error instanceof Error ? error.message : String(error)

}`,

);

}

},

};

And then this is what that tool looks like. It’s pretty much like the last one. There’s just a little more code because listing directories in Node.js is a little less convenient. But we have a name, a description, an input_schema that requires a path. Although the path is not required this time, it’s optional. We say in the instructions that if you don’t pass a path, we’ll list the current directory, which is a nice convenience.

And then over in the function on the right hand side, we check if the path exists and is a directory, and if so, we iterate through all of the entries. The one little extra we do here is that if an entry is a directory, we will output it with a slash on the end so that we provide a little clue here to the model of which things in the directory are sub directories or not. And that seems to work really well.

So let’s go ahead and demo this.

❯ git checkout demo5

❯ pnpm agent

vertexai-playground@1.0.0 agent /Users/kyank/Developer/how-to-build-an-agent-in-javascript

pnpm build && node dist/agent.jsvertexai-playground@1.0.0 build /Users/kyank/Developer/how-to-build-an-agent-in-javascript

tscChat with Claude (use ‘ctrl-c’ to quit)

You: What do you see in this directory?Claude: I’ll help you see what’s in the current directory. Let me check the contents for you.

Tool request: list_files({})

Claude: Do you want to continue? [yes]:Claude: The current directory contains a mix of files and directories:

Files:

- .envrc

- .gitignore

- .prettierignore

- .prettierrc.json

- README.md

- devbox.json

- devbox.lock

- package.json

- pnpm-lock.yaml

- secret-file.txt

- tsconfig.json

Directories:

- .git/

- dist/

- node_modules/

- src/

This appears to be a TypeScript/JavaScript project with standard configuration files, dependency management through pnpm, and a source directory (src/) where the code likely resides. There’s also a “secret-file.txt” which might contain sensitive information.

You:

What do you see in this directory? We’ll ask it.

I’ll check the what files and directories are present and it calls list files with no arguments, just as it should.

And there you go. It is reading my directories and it says, this appears to be a TypeScript JavaScript project using pnpm as a package manager with a devbox development environment setup. There’s also a file named secret-file.txt, which might contain sensitive information.

There you go. It’s done a pretty good job.

Um, how about, tell me about all the TypeScript files in this project.

You: Tell me about all the TypeScript files in here.

Claude: I’ll find and examine all the TypeScript files in this project. Let me start by checking for TypeScript files in the main directory and then look in the src/ directory where they’re most likely to be located.

Tool request: list_files({“path”:“src”})

Claude: Do you want to continue? [yes]:

It is guessing there might be TypeScript files in the src directory, which is a pretty good guess.

Claude: I found the src directory with a TypeScript file called “agent.ts” and an “agent” subdirectory. Let me check what’s in the agent subdirectory and then examine each TypeScript file.

Tool request: list_files({“path”:“src/agent”})

Claude: Do you want to continue? [yes]:Claude: I found more TypeScript files in the agent subdirectory. Let me also check if there are any TypeScript files in the tools directory:

Tool request: list_files({“path”:“src/agent/tools”})

Claude: Do you want to continue? [yes]:Claude: Now that I’ve found all the TypeScript files, let me examine each one to tell you about them:

Tool request: read_file({“path”:“src/agent.ts”})

Claude: Do you want to continue? [yes]:

And there’s a subdirectory called agent with my agent class in it, and there’s a sub subdirectory called tools with all of my tool definitions in it. It’s scanning all of those and now it’s requesting to read each of the files that it’s found in there.

Tool request: read_file({“path”:“src/agent/agent.ts”})

Claude: Do you want to continue? [yes]:Tool request: read_file({“path”:“src/agent/types.ts”})

Claude: Do you want to continue? [yes]:Tool request: read_file({“path”:“src/agent/tools/index.ts”})

Claude: Do you want to continue? [yes]:Tool request: read_file({“path”:“src/agent/tools/readFile.ts”})

Claude: Do you want to continue? [yes]:Tool request: read_file({“path”:“src/agent/tools/listFiles.ts”})

Claude: Do you want to continue? [yes]:

And it’s at this point that I start second guessing my caution of requiring an approval for every single tool call, but better safe than sorry.

Claude: Based on my examination of all the TypeScript files in this project, here’s what I found:

Project Overview

Permalink to Project OverviewThis is a TypeScript project that implements a Claude AI agent with tool integration. The agent can interact with users through a command-line interface and execute tools like reading files and listing directories.

TypeScript Files:

Permalink to TypeScript Files:

- src/agent.ts

- Main entry point that sets up an Anthropic Vertex AI client

- Creates an Agent instance with tools and UI handlers

- Implements UI functions for getting user input, showing messages, and asking for tool execution consent

- Uses Google Cloud’s “cross-camp-ai-enablement” project in “us-east5” region

- src/agent/agent.ts

- Defines the

Agentclass that handles the conversation flow- Manages the conversation state and message history

- Handles tool execution and user consent for tools

- Processes different types of content from Claude (text and tool_use)

- src/agent/types.ts

- Contains TypeScript type definitions for the project

- Defines the

ToolDefinitioninterface used to create tools- src/agent/tools/index.ts

- Exports an array of available tools (readFileTool and listFilesTool)

- src/agent/tools/readFile.ts

- Implements a tool for reading file contents

- Validates file existence and handles errors

- src/agent/tools/listFiles.ts

- Implements a tool for listing files in a directory

- Adds trailing slashes to directory names for clarity

The project demonstrates how to build a Claude agent with tool-calling capabilities. It uses the Anthropic Vertex AI client to connect to Google Cloud’s Claude API, and implements a command-line interface for interacting with the agent. The agent can execute tools that allow it to read files and list directories, with user consent required before any tool execution.

You:

And finally, there we go. A great big project overview. This is a TypeScript project that implements a Claude AI agent with tool calling capabilities. It creates an interactive command line interface where users can chat with Claude and allow it to execute specific tools. And it’s got a breakdown of what happens in each of the files.

Really good. Pretty neat.

Um, let’s try one more thing. What TypeScript version are we using in this project?

You: What TypeScript version are we using in this project?

Claude: To determine the TypeScript version being used in this project, I should check the package.json file, which typically contains information about dependencies including TypeScript. Let me examine that file.

Tool request: read_file({“path”:“package.json”})

Claude: Do you want to continue? [yes]:Claude: Based on the package.json file, this project is using TypeScript version 5.7.3, as indicated in the devDependencies section:

"devDependencies": { "@types/node": "^24.0.4", "prettier": "^3.4.2", "typescript": "^5.7.3" }The caret (^) before the version number means that the project will use at least version 5.7.3, but can automatically update to newer minor and patch versions within the 5.7.x range. However, the specific version being used is 5.7.3, which is a very recent version of TypeScript (as of the time this project was created).

What would you do if you were asked that question? Well, you would probably go and look in the package.json file, which is exactly what it does.

It’s identified TypeScript 5.7.3. Nice work.

Okay, so there we go. Using the two tools together.

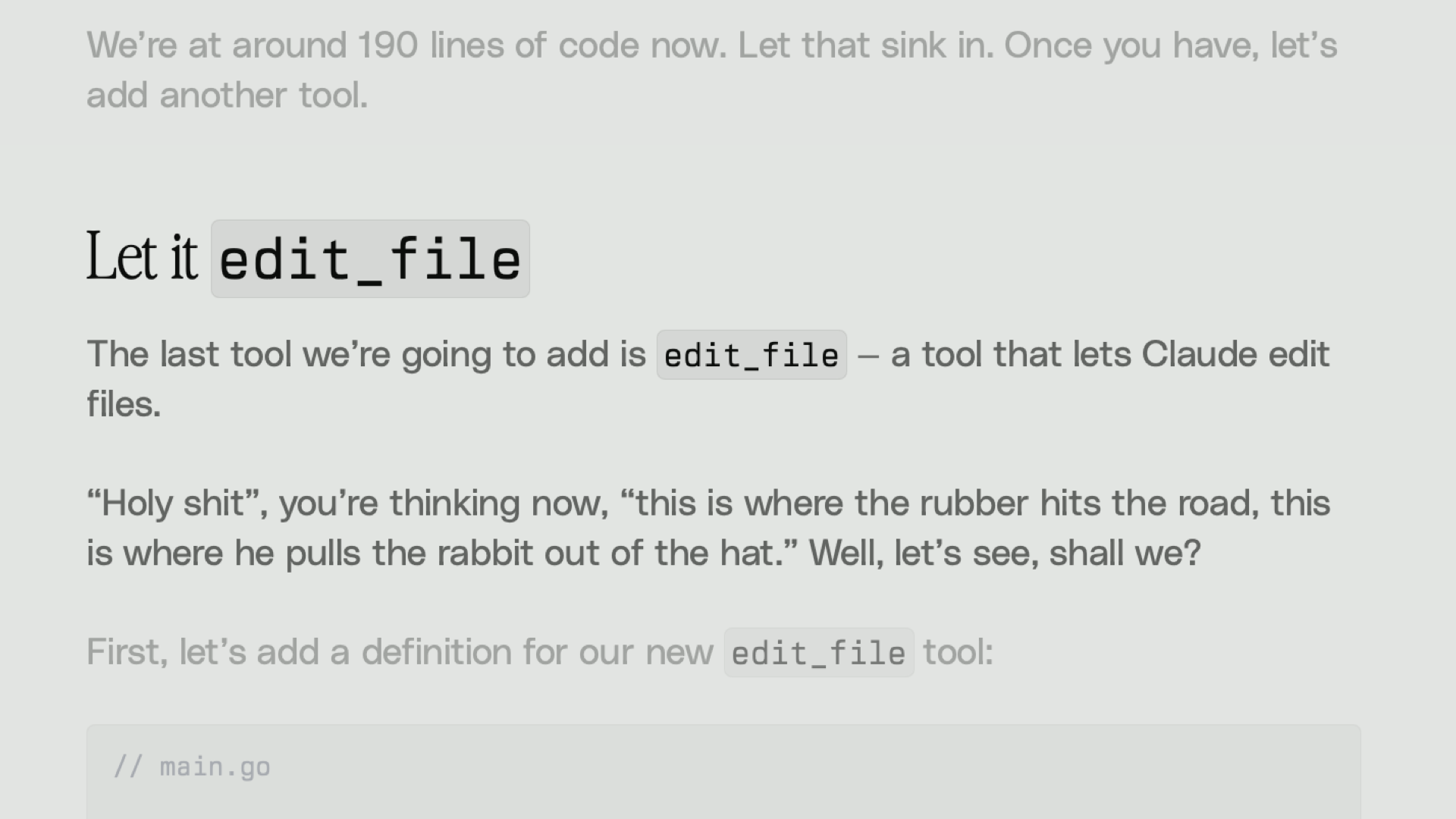

Let it edit_file

Permalink to

Let it edit_file

Now let’s let it edit files. The last tool we’re going to add is edit_file, a tool that lets Claude edit files. Holy shit, you’re thinking now, this is where the rubber hits the road. This is where he pulls the rabbit outta the hat. Well, let’s see, shall we?

import { readFileTool } from "./readFile.js";

import { listFilesTool } from "./listFiles.js";

import { editFileTool } from "./editFile.js";

export default [readFileTool, listFilesTool, editFileTool];

We create a new editFileTool.

/**

* Tool for editing file contents

*/

export const editFileTool: ToolDefinition = {

name: "edit_file",

description: `Make edits to a text file. Replaces

'old_str' with 'new_str' in the given file.

'old_str' and 'new_str' MUST be different from

each other. If the file specified with path

doesn't exist, it will be created.`,

input_schema: {

type: "object",

properties: {

path: {

type: "string",

description: "The relative path of a file in

the working directory.",

},

old_str: {

type: "string",

description: "The string to replace in the

file.",

},

new_str: {

type: "string",

description: "The string to replace with.",

},

},

required: ["path", "old_str", "new_str"],

},

func: async (args: any): Promise<string> => {

const path: string = args.path

const oldStr: string = args.old_str

const newStr: string = args.new_str

const resolvedPath = nodePath.resolve(path)

// Validate that old_str and new_str are different

if (oldStr === newStr) {

throw new Error(`'old_str' and 'new_str' must be

different from each other`)

}

try {

// EDIT THE FILE

} catch (error) {

throw new Error(error instanceof Error

? error.message

: String(error)

)

}

}

}

And here’s the structure of this file. We’ll say that it’s a tool that lets you make edits to a text file. It replaces old string with new string in the given file. Old string and new string must be different from each other. If the file specified with the path doesn’t exist, it will be created.

And then in func we check that old string and new string are different. And if they are, then we will attempt to edit the file. I’ve put the code for that on a separate slide 'cause it’s a little too long to fit.

let fileContent: string;

// Check if file exists

if (existsSync(resolvedPath) && oldStr !== "") {

// Read existing file content

fileContent = await fs.readFile(resolvedPath, "utf-8");

// Check if old_str exists in the file

if (!fileContent.includes(oldStr)) {

return `No changes made:

String '${oldStr}' not found in the file.`;

}

// Replace all occurrences of old_str with new_str

const splitParts = fileContent.split(oldStr);

const newContent = splitParts.join(newStr);

// Write the modified content back to the file

await fs.writeFile(resolvedPath, newContent, "utf-8");

// Count replacements:

// splitParts.length - 1 gives the number of

// delimiters (oldStr) found

const occurrences = splitParts.length - 1;

return `Successfully made ${occurrences}

replacement${occurrences !== 1 ? "s" : ""}

in ${path}`;

} else if (oldStr === "") {

await fs.writeFile(resolvedPath, newStr, "utf-8");

return `Created new file ${path} with the provided

content`;

}

// Throw error for the case where the file doesn't exist and oldStr is not empty

throw new Error(`File ${path} does not exist.`);

So we will check if the file with the given path exists, and if so, we make sure that the old string is not empty. We then read the contents of the file, find every occurrence of old string, and replace it with new string, and return a string that summarizes what we’ve done by counting the number of replacements.

If the file didn’t exist and old string is empty, then we create a new file with new string as the contents. And if none of those things happen, then we throw an error because we are trying to edit a file that doesn’t exist.

That’s it. That’s our editing tool. Let’s demo it.

❯ git checkout main

❯ pnpm agent

vertexai-playground@1.0.0 agent /Users/kyank/Developer/how-to-build-an-agent-in-javascript

pnpm build && node dist/agent.jsvertexai-playground@1.0.0 build /Users/kyank/Developer/how-to-build-an-agent-in-javascript

tscChat with Claude (use ‘ctrl-c’ to quit)

You: Hey Claude, create fizzbuzz.js that I can run with Node.js and that has fizzbuzz in it and executes it.Claude: I’ll create a fizzbuzz.js file for you that can be run with Node.js. The FizzBuzz program prints numbers from 1 to n, but for multiples of 3 it prints “Fizz”, for multiples of 5 it prints “Buzz”, and for multiples of both 3 and 5 it prints “FizzBuzz”.

Let me create this file for you:

Tool request: edit*file({“path”:“fizzbuzz.js”,“old_str”:“”,“new_str”:“/**\n * FizzBuzz implementation\n _ Prints numbers from 1 to 100\n _ For multiples of 3, prints "Fizz" instead of the number\n _ For multiples of 5, prints "Buzz" instead of the number\n _ For multiples of both 3 and 5, prints "FizzBuzz"\n _/\n\nfunction fizzBuzz(n) {\n for (let i = 1; i <= n; i++) {\n if (i % 3 === 0 && i % 5 === 0) {\n console.log(‘FizzBuzz’);\n } else if (i % 3 === 0) {\n console.log(‘Fizz’);\n } else if (i % 5 === 0) {\n console.log(‘Buzz’);\n } else {\n console.log(i);\n }\n }\n}\n\n// Execute FizzBuzz for numbers 1 to 100\nconsole.log(‘Running FizzBuzz from 1 to 100:’);\nfizzBuzz(100);”})

**Claude:** Do you want to continue? [yes]:Claude: I’ve created a file named

fizzbuzz.jswith a FizzBuzz implementation. The code:

- Defines a

fizzBuzzfunction that takes a numbernas input- Iterates from 1 to n

- For each number:

- If divisible by both 3 and 5, prints “FizzBuzz”

- If divisible by 3, prints “Fizz”

- If divisible by 5, prints “Buzz”

- Otherwise, prints the number itself

- Executes the function for numbers 1 to 100

You can run this file with Node.js by using the following command in your terminal:

node fizzbuzz.jsThis will display the FizzBuzz sequence from 1 to 100 in your console.

You:

Hey, Claude, create fizzbuzz.js that I can run with Node.js and that has fizzbuzz in it and executes it.

This is a pretty typical, um, interview question for programmers. There is the implementation of Fizzbuzz in JavaScript that it wants to write into a fizzbuzz.js file. Looks good to me.

Now if you don’t know if Fizbuzz, uh, it has described it up there, what it does. Multiples of three will be output as fizz, multiples of five as buzz, multiples of both as fiz buzz. Otherwise, it’ll just output the numbers. Yes, we will let it read the file to confirm that it was created correctly. And it reckons it’s all done.

It even tells me how to run it. So let’s accept the invitation.

❯ node fizzbuzz.js

Running FizzBuzz from 1 to 100:

1

2

Fizz

4

Buzz

Fizz

7

8

Fizz

Buzz

11

Fizz

13

14

FizzBuzz

16

17

Fizz

19

Buzz

Fizz

22

23

Fizz

Buzz

26

Fizz

28

29

FizzBuzz

31

32

Fizz

34

Buzz

Fizz

37

38

Fizz

Buzz

41

Fizz

43

44

FizzBuzz

46

47

Fizz

49

Buzz

Fizz

52

53

Fizz

Buzz

56

Fizz

58

59

FizzBuzz

61

62

Fizz

64

Buzz

Fizz

67

68

Fizz

Buzz

71

Fizz

73

74

FizzBuzz

76

77

Fizz

79

Buzz

Fizz

82

83

Fizz

Buzz

86

Fizz

88

89

FizzBuzz

91

92

Fizz

94

Buzz

Fizz

97

98

Fizz

Buzz

There we go. A working fizz buzz.

Uh, there’s more to try though. Let’s actually edit this file. Um, that fizzbuzz to 100 is a little long.

❯ pnpm agent

vertexai-playground@1.0.0 agent /Users/kyank/Developer/how-to-build-an-agent-in-javascript

pnpm build && node dist/agent.jsvertexai-playground@1.0.0 build /Users/kyank/Developer/how-to-build-an-agent-in-javascript

tscChat with Claude (use ‘ctrl-c’ to quit)

You: Please edit fizzbuzz.js so that it only prints until 15Claude: I’ll help you edit the fizzbuzz.js file to only print until 15 instead of its current limit. First, let me check the current content of the file to understand what needs to be changed.

Tool request: read_file({“path”:“fizzbuzz.js”})

Claude: Do you want to continue? [yes]:Claude: Now I’ll edit the file to change the limit from 100 to 15. I need to modify the comment at the top and the function call at the bottom:

Tool request: edit*file({“path”:“fizzbuzz.js”,“old_str”:“/**\n * FizzBuzz implementation\n _ Prints numbers from 1 to 100\n _ For multiples of 3, prints "Fizz" instead of the number\n _ For multiples of 5, prints "Buzz" instead of the number\n _ For multiples of both 3 and 5, prints "FizzBuzz"\n _/”,“new_str”:“/**\n _ FizzBuzz implementation\n _ Prints numbers from 1 to 15\n _ For multiples of 3, prints "Fizz" instead of the number\n _ For multiples of 5, prints "Buzz" instead of the number\n _ For multiples of both 3 and 5, prints "FizzBuzz"\n _/”})

Claude: Do you want to continue? [yes]:Tool request: edit_file({“path”:“fizzbuzz.js”,“old_str”:“// Execute FizzBuzz for numbers 1 to 100\nconsole.log(‘Running FizzBuzz from 1 to 100:’);\nfizzBuzz(100);”,“new_str”:“// Execute FizzBuzz for numbers 1 to 15\nconsole.log(‘Running FizzBuzz from 1 to 15:’);\nfizzBuzz(15);”})

Claude: Do you want to continue? [yes]:Claude: I’ve successfully modified the fizzbuzz.js file to only print up to 15 instead of 100. The changes made were:

- Updated the comment at the top to state that it “Prints numbers from 1 to 15” instead of 1 to 100

- Changed the execution line from

fizzBuzz(100)tofizzBuzz(15)- Updated the console.log message to say “Running FizzBuzz from 1 to 15:” instead of “…to 100:”

The FizzBuzz function itself didn’t need to be changed as it was already parameterized to accept a limit (n) and will now stop at 15 as requested.

You:

Uh, please edit fizzbuzz.js so that it only prints until 15. That should fit on the screen. It is gonna list the files in the directory to make sure that file is there.

It’s gonna read it, it’s gonna edit it. There we go. It’s use all three of our tools. It’s gonna edit it, edit it again to make another change, and it thinks it’s done. Let’s see if it’s right.

❯ node fizzbuzz.js

Running FizzBuzz from 1 to 15:

1

2

Fizz

4

Buzz

Fizz

7

8

Fizz

Buzz

11

Fizz

13

14

FizzBuzz

There we go, a working fizzbuzz from one to 15.

Let’s do one more. In this one, from Thorson, we’re gonna ask it to create a congrats.js script that rot13 decodes this string and prints it. If you don’t know rot13 it’s a very weak encryption algorithm that just shifts every letter in the alphabet by 13 uh spaces in order to make an indecipherable string.

❯ pnpm agent

vertexai-playground@1.0.0 agent /Users/kyank/Developer/how-to-build-an-agent-in-javascript

pnpm build && node dist/agent.jsvertexai-playground@1.0.0 build /Users/kyank/Developer/how-to-build-an-agent-in-javascript

tscChat with Claude (use ‘ctrl-c’ to quit)

You: Create a congrats.js script that rot13-decodes the following string ‘Pbatenghyngvbaf ba ohvyqvat n pbqr-rqvgvat ntrag!’ and prints itClaude: I’ll create a JavaScript script that decodes a rot13-encoded string and prints it.

Let me first create the congrats.js file with the code to decode and print the string ‘Pbatenghyngvbaf ba ohvyqvat n pbqr-rqvgvat ntrag!’.

Tool request: edit*file({“path”:“congrats.js”,“old_str”:“”,“new_str”:“/**\n * A script that decodes a rot13-encoded string and prints it\n _/\n\n// The encoded string to decode\nconst encodedString = ‘Pbatenghyngvbaf ba ohvyqvat n pbqr-rqvgvat ntrag!’;\n\n/**\n _ Function to decode a rot13-encoded string\n _ @param {string} str - The rot13-encoded string\n _ @return {string} The decoded string\n _/\nfunction rot13Decode(str) {\n return str.replace(/[a-zA-Z]/g, function(char) {\n // Get the character code\n const charCode = char.charCodeAt(0);\n \n // Handle uppercase letters (A-Z: 65-90)\n if (charCode >= 65 && charCode <= 90) {\n return String.fromCharCode(((charCode - 65 + 13) % 26) + 65);\n }\n \n // Handle lowercase letters (a-z: 97-122)\n if (charCode >= 97 && charCode <= 122) {\n return String.fromCharCode(((charCode - 97 + 13) % 26) + 97);\n }\n \n // Return non-alphabetic characters unchanged\n return char;\n });\n}\n\n// Decode and print the string\nconst decodedString = rot13Decode(encodedString);\nconsole.log(decodedString);”})

Claude: Do you want to continue? [yes]:Claude: Now let me verify the content of the file:

Tool request: read_file({“path”:“congrats.js”})

Claude: Do you want to continue? [yes]:Claude: I’ve created the congrats.js script that:

- Defines the rot13-encoded string ‘Pbatenghyngvbaf ba ohvyqvat n pbqr-rqvgvat ntrag!’

- Implements a rot13Decode function that:

- Processes each alphabetic character in the string

- Shifts each letter by 13 positions in the alphabet

- Preserves case (uppercase/lowercase)

- Leaves non-alphabetic characters unchanged

- Decodes the string and prints the result to the console

When you run this script with Node.js (using the command

node congrats.js), it will decode and display the hidden message.Note: The rot13 cipher is a simple letter substitution that replaces each letter with the letter 13 positions after it in the alphabet, wrapping around if necessary.

You:

That’s exactly what it’s going to do in the JavaScript code.

So let’s exit and node congrats.js.

❯ pnpm agent Congratulations on building a code-editing agent!

Congratulations on building a code editing agent. So there we go.

Isn’t this amazing?

Permalink to Isn’t this amazing?

At the end of this article, it says, isn’t this amazing? If you’re anything like all the engineers I’ve talked to in the past few months, chances are that while reading this, you have been waiting for the rabbit to be pulled out of the hat, for me to say, well, in reality, it’s much, much harder than this, but it’s not.

This is essentially all there is to the inner loop of a code editing agent. Sure, integrating it into your editor, tweaking the system prompt, giving it the right feedback at the right time, a nice UI around it. Better tooling around the tools, support for multiple agents and so on. We’ve built all of that in Amp, but it didn’t require moments of genius.

All that was required was practical engineering and elbow grease. These models are incredibly powerful now. 300 lines of code – it’s more like 400 in Node.js, for the record – and three tools and now you’re able to talk to an alien intelligence that edits your code. If you think, well, but we didn’t really, go ahead and try it.

Go and see how far you can get with this. I bet it’s a lot farther than you think. That’s why we think everything’s changing.

If you wanna take this project for a spin, you can find the link to the GitHub project with the source code in the description of this video or in the blog post where you’re viewing it.

And if you want to read the original article, I invite you to go and visit the Amp Code blog.

So there you go. The blog post of the year for 2025. I can’t say I disagree, and I’m happy it exists in TypeScript now. Hope you enjoyed it. Thanks for watching.